Why British Endurance Running Did So well in Tokyo 2020

- Barry Fudge

- Aug 11, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2021

For the first time in 33 years, more than one British (GBR) athlete has won a medal at the Olympic Games in endurance running events.

Since 1988, where GBR won 4 medals from 4 different athletes, they have won 7 medals from just 2 athletes, Mo Farah and Kelly Holmes. Small numbers in contrast to some other Olympic sports, but for perspective, to win an Olympic medal on the track is arguably the hardest medal to win at the Games due to the depth of countries who compete (i.e. every country in the World) and the access to the sport (i.e. people can run pretty much anywhere, even without shoes). In Tokyo GBR had medals from Laura Muir (1,500m — Silver), Keely Hodgkinson (800m, Silver) and Josh Kerr (1,500m — Bronze) that went hand-in-hand with an 850% increase in athletes capable of medalling compared to just a decade ago. As the Head of Endurance at British Athletics from 2013–2020, this is why I believe there has been success at the most recent Games.

When I took on the lead role in late 2013, GBR were living off the gold dust of Mo Farah who had just won his 3rd World title in Moscow and was the double Olympic Champion from the year before. “Double — Double”, something no other man has ever done before in endurance running events, so we all could be forgiven for thinking everything was on track in endurance. But after the 2013 Moscow World Championships, I started to examine the talent pathway and began to recognise that there probably wasn’t enough talent coming through after Mo Farah to fill the gap that he would leave behind when he eventually retired. I had done my PhD in Kenya and Ethiopia and knew their success on the Global stage was partly due to a numbers game.

Figure 1: Simplified talent pathway. Medal Zone athletes are capable of running a season’s best time that is historically required to medal at a Global Championships. Olympic standard athletes are capable of qualifying for the Olympics whilst Elite standard athletes are capable of running a time that would rank them within the top 10 in the UK. National standard athletes are capable of running a time that would rank them within the top 100 in the UK.

Figure 1 displays a simplified model of an athletic talent pathway. It is typically presented as a pyramid as the top level tends to be smaller in number than the layers below. That is, there are significantly fewer people in the UK capable of winning a medal vs. those that are capable of making the top 100 in the UK.

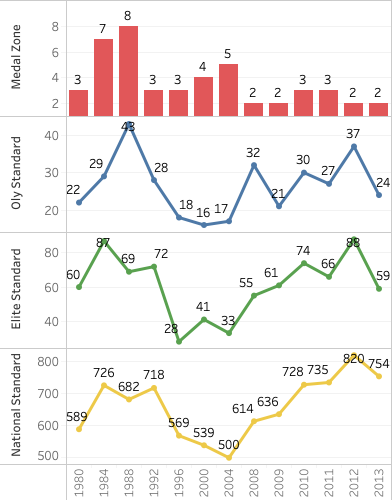

Figure 2: GBR pathway data 1980-2013.

Figure 2 presents the number of athletes at each level of the pathway for UK runners in events from 800m to marathon from 1980 to 2013. Taking a typical 15–20% conversion rate of Medal Zone athletes to medalists at a Global Championships, the data didn’t look too great for now and the future! Just 2–3 Medal Zone athletes at best would equate to 0-1 medal. So in actual fact, GBR were lucky to have a super-star like Mo Farah to (almost) guarantee 2 medals at every Championships he went too. But I and Neil Black (the previous UKA Performance Director) were all to aware that this wouldn’t last forever and we needed a strategy to try and close the gap in the coming years. A task we knew from experience would not happen overnight but would take years to come to fruition. And 2020 was likely when it needed to come together. The future of the sport would be dependent on it, not only from a financial perspective but also to inspire and motivate the next generation of athletic stars.

In 2013, the strategy set for the Endurance program focused on two main aspects. First to increase the density of the athletes in the pathway and secondly, to improve the effectiveness of the support provided to the athletes. The first aim was based on the basic philosophy that for there to be more Medal Zone athletes at the top of the pyramid (Figure 1), there probably needed to be more athletes at all levels of the pathway in order to create upward pressure to move things forward. The second aim was based on an acknowledgement that we needed to improve the effectiveness of the support provided to those athletes if we wanted the pathway to be sustainable and progressive. UK Sport money could only be used on a select few (approximately 10 athletes at that time) but with the financial support of the London Marathon (over and above Lottery funding), we set out to meet those aims by investing in a large number of identified athlete and coach pairs across the whole pathway, aligned with objective and performance led targets. At the same time we also seeked to grow and develop British coaching as well as practitioner resources, both of which underpin and support athletes. Lastly, we focused on creating and supporting conducive environments for performance. In particular, we implemented an altitude strategy that is now producing significant gains in performance (that’s for another article).

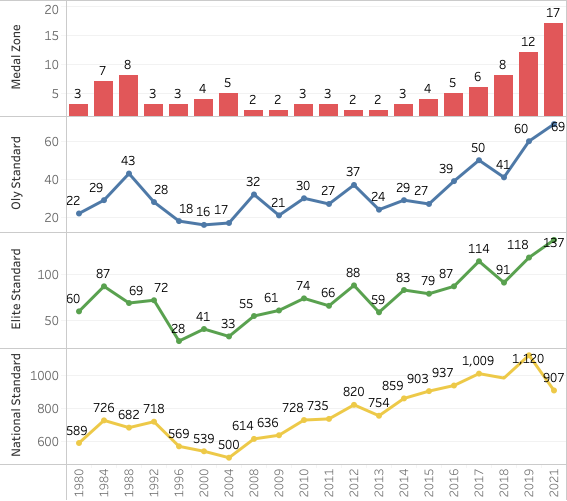

Figure 3: GBR pathway data 1980–2021 (National level is down in 2021 as this number is usually calculated at the end of the season — there is still 4–5 weeks left — and will likely increase).

As Figure 3 shows, GBR has seen significant growth at all levels of the Endurance pathway. The upward pressure on the pathway has resulted in a significant number of Medal Zone athletes in the pathway. An 850% increase! That is more than double the amount of athletes in the heydays of the 80’s. In addition, there are almost double the amount of athletes running Olympic standards now compared to the 2012 Olympiad which resulted in the largest Endurance squad at a Games in a generation despite tightening World Athletics Standards (which has a significant effect on other event groups).

In real terms this means that to make the GBR team for a Championships you have to be one of the best in the World. So if you make the team, you have a high chance at medalling.

A significant portion of the gains have been made in the middle distances which is why trials were so hotly contested in these events this year. And subsequently, why medals were won in Tokyo from the middle distances. This is of course backed up by the results of the early 80’s when we had fierce competition in the men’s middle distances in the UK which resulted in Global medals by the bucketload.

So whilst it may appear that some of these performances have come out of nowhere for GBR, they have in actual fact come from a carefully executed succession plan that started 8 years previously.

With the current crop of athletes, at all levels of the pathway, it really could be a golden generation for endurance running fans in the UK. That said, it is not enough to simply have the numbers in the current proffesional era (e.g. just look at Kenya and Ethiopia’s relative results this year). The margins are tight, the competition fierce and those athletes and their coaches need significant support to be successful. Hard cash, science and medicine resources and of course leadership and experience to help navigate what is a tough schedule over the next 3 year cycle in to Paris 2024. And I don’t just mean the top athletes that UK Sport will support. As the above shows, all levels need support. But with less money in the sport than for as long as I can remember (i.e. no London Marathon support for non funded athletes like before, minimal sponsorship for athletes as well as the Federation and of course, reduced Lottery Funding), as well as limited elite athletics leadership experience in the performance team and at board level, it is going to be a big ask. Those in charge need to do something that has never been done before to convert a number of medallists whilst continuing to build the pathway. Time will tell if their new model and leadership team will work. Let’s hope it does. Otherwise we are looking at a wasted generation.

Comments